THE POETICS OF PLAY

For Tamara Toumanova by Joseph Cornell c.1940

The creative writer has two courses open to him: either to seek what security and comfort there is for him in past configurations of learning, or to follow his great constructive genius into his own world.

— William Carlos Williams, Recognizable Image, 1978

When I enrolled onto the Writing Poetry MA at Newcastle University in 2018, I had no idea where my education in poetry would take me. Over the last two years, I've gained a deeper understanding of the creative possibilities of poetry than I ever imagined I would, and walked through doorways that I never knew existed, let alone ever expected to find. In May 2019, a few months after joining the course, I attended several events hosted by the Newcastle Poetry Festival, through which I discovered a number of poets and poetic practices that were hitherto unknown to me. One of these events was the Northern Poetry Symposium, during which co-editor of Haverthorn Press, Iris Colomb, shared some of the creative processes involved in the making of her visual poetry series and performance piece, Just Promise You Won’t Write (Gang Press 2019).

In chapbook form, Just Promise you Won't Write consists of nine scanned images of piles of shredded text, much of which is illegible. That which is legible is fragmented and disparate, posing a challenge to a widely accepted definition of poetry as “composition in verse or some comparable patterned arrangement of language in which the expression of feelings and ideas is given intensity by the use of distinctive style and rhythm” (OED Online). Rather than expressing feelings and ideas or utilising techniques such as rhythm, Colomb’s work resists the usual formal and intellectual expectations of poetry, offering instead a body of work in which language is not only difficult to grasp but, in some respects, meaningless. Enlivened by the unapologetic radicalism of Colomb’s poetry, I promised myself that I would have a go at not writing and started to consider the unwritten forms that my own work might adopt.

Just Promise you Won’t Write by Iris Colomb

At the time of the symposium, Just Promise You Won’t Write was not only the most experimental poetry book that I had come across, but wholly unlike anything that I had experienced in literature in general. Since then, I've discovered a number of poets whose work involves the use of image as well as text, and enjoyed playing with a range of visual media to create poems which, like theirs, exist at the intersection of literature and visual art.

While I don't consider myself a member of any poetry movement or collective per se, the creative work that I'm currently producing is reflective of an experimental approach. Describing myself as an “experimental poet” isn't something that I currently feel comfortable with as my practice involves a wide range of forms and techniques, some of which aren't in the least bit unexpected. However, over the last year I've enjoyed integrating into the British Innovative Poetry community where I've found a hugely inspiring and supportive network of established writers and artists including Astra Papachristodoulou, Steven J Fowler, James Knight (aka The Bird King), and Richard Capener, among many others. Engaging with their endlessly fascinating work online and in print has helped me to better understand where and how my own work fits into the contemporary poetry landscape.

From Chimera by James Knight

From Astropolis by Astra Papachristodoulou

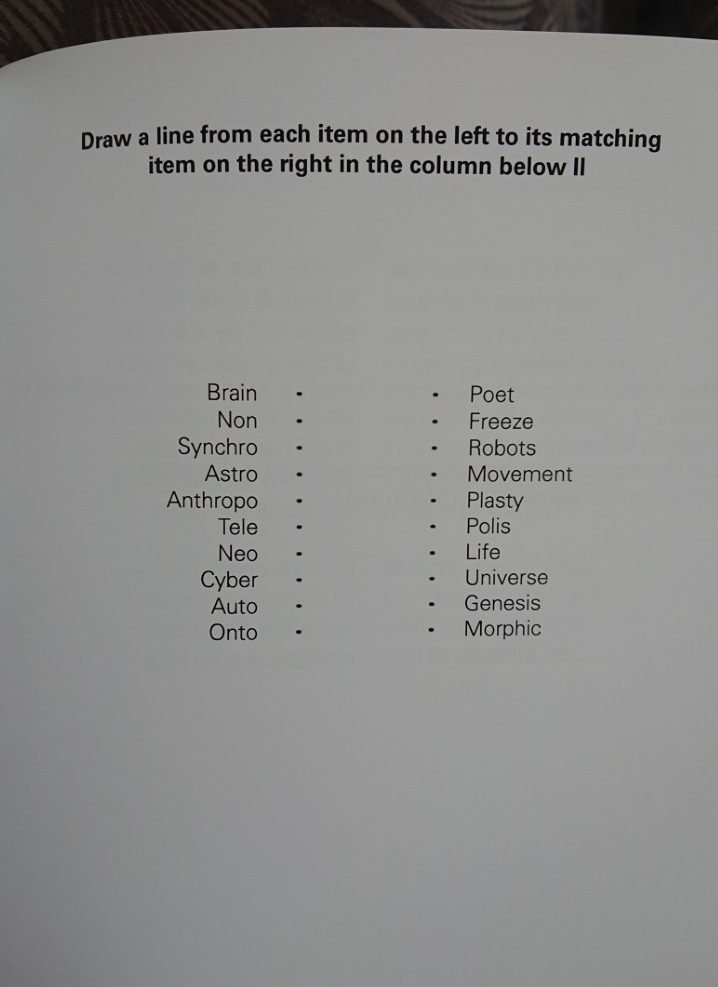

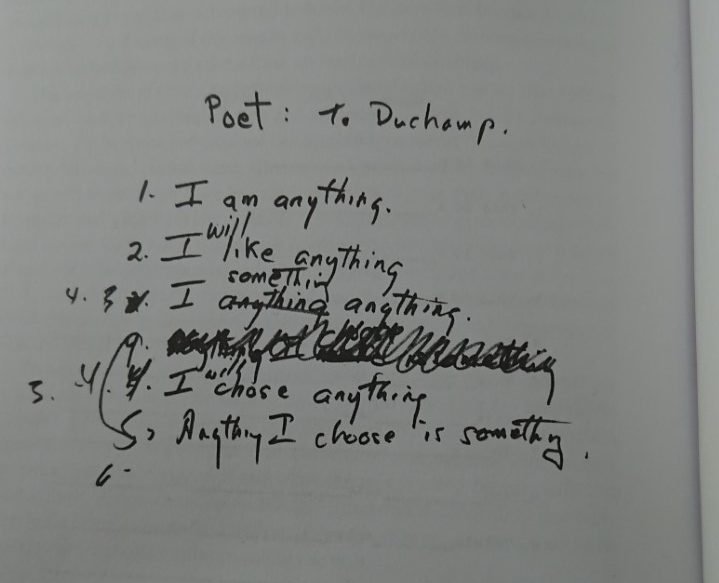

In the recently published expanded edition of her 2018 visual poetry collection, Astropolis (Hesterglock Press 2020), Papachristodoulou includes a twelve-step manifesto for creating what she defines as “Neo-Futurist” poetry. While my work doesn't wholly adhere to “Neo-Futurist” expectations and constraints, some of the manifesto’s guidance does align with how I'm currently choosing to create new work. Particularly relevant is the idea that poems should interact with the reader as much as possible, and the suggestion that poets should experiment with new forms, discover new practices, use objective rather than subjective discourse, and embrace new themes.

Of the 100 or so poems that I created for the MA, my film poem, “Story of the Shells #2,” is probably the best example of how some of these ideas have been put into practice in my work. Involving not only the cleaning, drilling, painting, glossing, stringing together, and filming of oyster shells left over from a friend’s birthday dinner, but the creation of a purpose-written text-based poem titled “Story of the Shells,” this piece exemplifies my ongoing commitment to exploring new forms and creative processes. Inspired by object poems such as Papachristodoulou’s “artificial honeycomb” (Astropolis 70) and Julia Nakotte’s “afternoon dream” (Poem Atlas), the home-crafted oyster shell mobile that features in “Story of the Shells #2” is as much a beautiful ornament as it is a poem or a piece of art, epitomising the multiplicity of purpose by which object poems are characterised.

Story of the Shells #2, 2020

Other poems of mine that take on object-like forms are those created via erasure. In “A Process of Illumination: Conversations about Erasure Poetry,” B.J. Best and C. Kubusta suggest that working with erasure is “a way to encourage playfulness with language, to introduce the idea that we write from the material that exists around us, that maybe writing isn’t some rarified activity of geniuses who hand down wisdom in ornate forms and perfect cadence.” After discovering Mary Reufle’s erasure poems, also at the 2019 Northern Poetry Symposium, I became keenly interested in the idea that poetry can be created from existing texts, and that making poems does not have to involve generating new and complex ideas through my own vocabulary.

An aspect of working with erasure that I find hugely appealing is the process that it necessitates, which, unlike that of writing from scratch, involves finding rather than thinking of language. Once I've chosen a text to work with, I begin by familiarising myself with its contents, reading the introduction if there is one and taking note of any intriguing chapter titles and headings. When included, chapter titles and headings are incredibly useful as they can help to direct my attention towards a certain theme or idea, which can in turn make the poem that little bit easier to find. The next step involves scanning the pages for suitable language. This is the most time-consuming part of the process, requiring a huge amount of mindful concentration. In a 2016 interview with Katherine Stingley Reufle describes it as meditative. For me, it feels more like slightly frantic daydreaming.

A Little White Shadow by Mary Reufle

What I'm looking for when I scan is a strong image or something that I can use to create a setting or a character. Pronouns and nouns are extremely helpful. After settling on a word or phrase that feels promising, I continue to search for whatever's missing. Just as trying to write a new piece of work can take a long time and sometimes leads to nothing more than a page of crossed out words, so too can trying to create an erasure poem be hugely time-consuming and unfruitful. Every page can be reworked into a new piece of text, but not every new piece of text can be defined as a poem. This is usually because the found language fails to transform the original work in a meaningful way; if I have a good reason for choosing erasure over another form, it's important to me that any poems I make with the source material communicate this in some way.

An important consideration when working with erasure is which materials will be used to erase the unwanted text. In her 2012 work, Melody (Gwarlingo 2012), Reufle uses white correction fluid and embellishes the pages with small objects or cut-outs from second-hand books, while Yasmine Seale makes use of a variety of materials, from sand and household string to drawings and magazine cuttings. When making my own work, I allow the content and context of each poem to guide my decision. In most cases, the neutrality of white correction fluid is all that's needed to bring the found text into prominence. However, some pieces call for something more specific. In my poem, “Preference by the Female” (made using page 467 of Charles Darwin's The Descent of Man), a scattering of soil points to the existence of a world beyond the confines of the page, while thick layers of torn masking tape in “The First Dream” (made using page 65 of Sigmund Freud's A Case of Hysteria) evoke a sense of concealment in line with the poem’s imagery.

These visual poems, along with several others, form part of a series titled “Corrections” in which well-known texts by influential authors are reworked into poems which challenge their theories and observations. Bearing this in mind, it's been incredibly important that I commit to creating poems that not only change but overtly challenge the original work.

The First Dream

A Case of Hysteria

In addition to experiments with erasure, objects, and other forms of visual media, I’ve also worked hard throughout the MA to better understand the techniques and processes that are involved in the making of successful text-based poetry. In a 2016 interview with Poetry Spotlight, Fowler states that “the reader has an enormous role to play in the meaning of a poem through their endless, idiosyncratic individual experience of language and its impossibly intricate potential in their minds and memories.” Until recently, I was frequently guilty of over-explaining and over-embellishing my poems, too often leaving little for the reader to unpack and make their own. Reading Madeline Gins’s experimental poems and an introduction to her work by Lucy Ives in the April 2020 issue of POETRY magazine initiated a dramatic re-evaluation of how I view the role of the reader, and encouraged me to revise several pieces that I had considered finished.

The edits that followed are hugely important, as they enable readers to absorb my poems through the lens of their own experiences and responses rather than through mine, as should always be the case. As French philosopher and experimental writer Phillipe Sollers posits in Writing and the Experience of Limits, “a work exists by itself only potentially, and its actualization (or production) depends on its readings and on the moments at which these readings actively take place [sic].”

From POETRY, April 2020

As well as introducing me to fabulous creative techniques such as leaving blank spaces for readers to fill in, engaging with Gins's poetry also contributed to the relatively recent decision that I took to abandon the self-enclosed "lyric I" of confessional style poetry and focus instead on communicating through objective discourse, as is also recommended in Papachristodoulou’s manifesto. Oscar Wilde is often credited with suggesting that “all bad poetry springs from genuine feeling;” based on what I've learned about my own poetry writing process over the last two years, I'm inclined to agree.

I began my education at Newcastle feeling that as long as I was content with my work then what others made of it was largely unimportant; I'm leaving the MA with my mind firmly changed. Choosing to prioritise the reader’s experience has not only increased the frequency with which my work is selected for publication but enabled me to integrate into an exciting poetry community within which exploration of the unfamiliar is not only welcomed but strongly encouraged. Through learning how to play, I've discovered how to gift my poetry to others. As I transition into the next stage of my career, continuing to give away rather than stubbornly hold on to my poems will ensure that I'm able to find, and to open, all the right doors.